At under 260 pages, the easily accessible novel is a classic and beloved piece of literature most people have never read, perhaps explaining why it has escaped our collective consciousness how bad the book is and how it completely fails to prove its central point.

Golding himself said he wanted to “trace the defect in human society back to the defect of human nature.”

Ironically, its defective character building and a total lack of moral introspection which send Golding’s thesis crashing into the sand harder than the boys’ ill-fated aircraft.

To prove society is innately evil or “defective” you need, at least, a representative sample of society, in this case, school age boys, as well as time to let the hidden virus slowly consume them from the inside out.

Golding gives us neither.

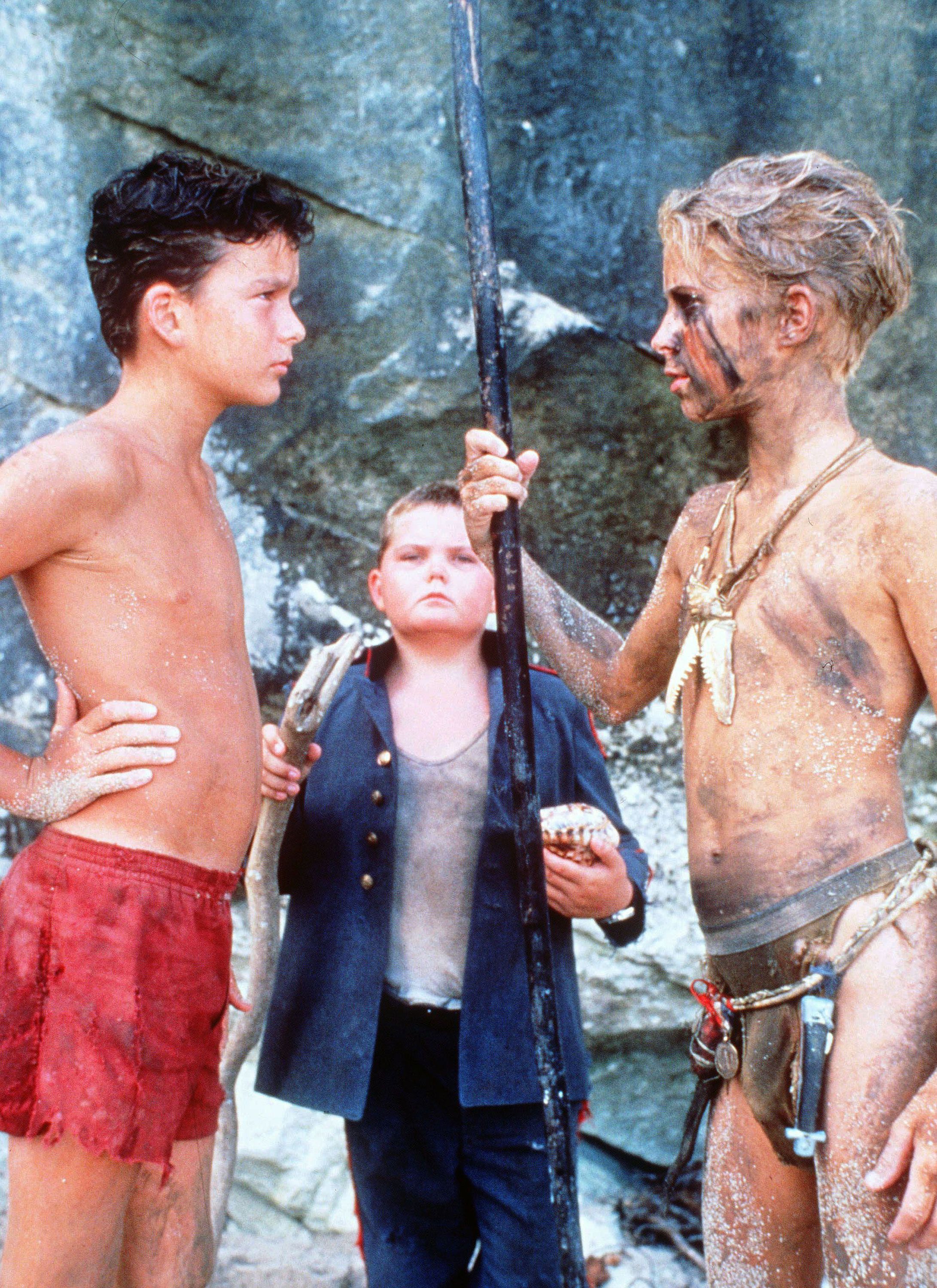

Instead, the audience is inflicted with Jack Merridew, the book’s principal antagonist, who far from being a saint-turned-savage, appears to have crash-landed on the island as some sort of junior sociopath in training.

From Jack’s first appearance to his last, he is prideful, antagonistic, violent, and cruel, a critical error which undermines Golding’s entire thought experiment.

Pick twenty random teenagers from a cross-section of society, drop them off in the middle of nowhere, and you have the beginnings of a universal morality tale.

But if one of those teens has the moral bearings of David Koresh or Jim Jones, you no longer have an allegory for the human experience, but a very specific “surviving Jack Merridew” thriller novel.

These unfortunate children don’t have an insuperable problem of innate human wickedness; they have a problem with a flatly evil character with no nuance.

Take him out of the equation and you erase the conflict, erasing the book’s general applicability to society.

As far as the question of time, given minor details about hair growth and the deterioration of clothes, we can assume the boys were on the island several months (though somehow still not long enough for “Piggy”, the group’s oft-ignored voice of reason, to have lost any considerable amount of weight, despite only subsisting on a diet of fruit and water, a glaring plot hole which conveniently provided copious amounts of sadistic fodder for Golding’s kids).

Golding wants us to believe that in less than a year, his adolescent boys have so decayed that they literally rip, bite, and beat to death one of their peers with nothing more than simping half-hearted guilt on the part of a handful of kids afterwards.

It’s not that I cannot imagine how a group of kids could arrive at that level of savagery; it’s that I shouldn’t have to imagine, hence the book.

Golding’s novel is not a slow descent into madness, but a sprint, hurtling past every opportunity to give the reader necessary insight into the formation of the new morality which emerges from the vacuum of the group's isolation.

As easily as I can imagine the moral collapse of such a newly formed society, I can also imagine a group of kids who imperfectly band together for the sake of survival (see the old Disney show Flight 29 Down, which turns the pessimistic premise of Lord of the Flies on its head)

Tell me why should I buy into Golding’s version of humanity?

By skimping on the plot, Golding takes a fascinating and fruitful idea and leaves it to sizzle in the tropic sun.